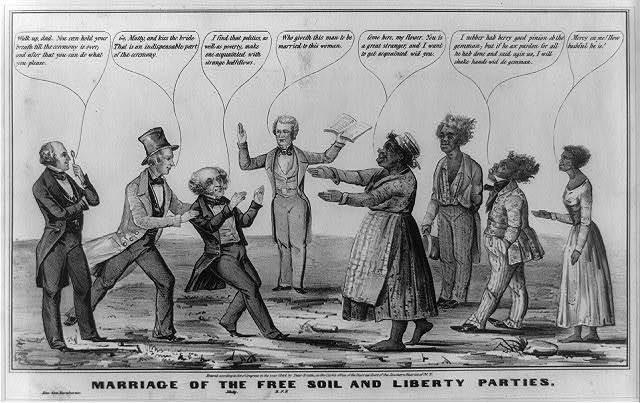

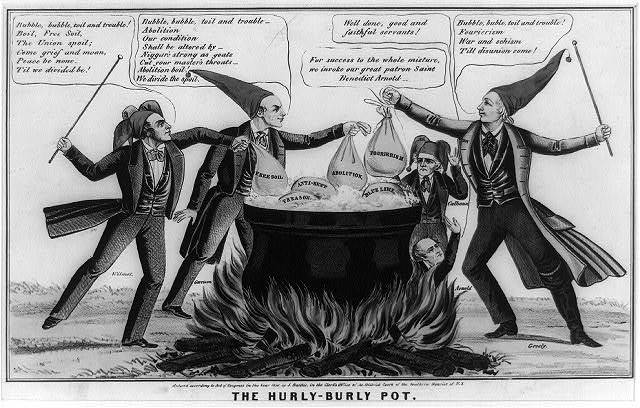

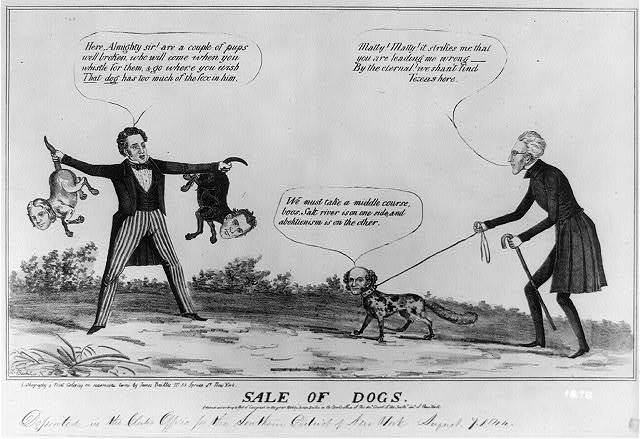

Although antislavery political parties did not debut until the 1840s, abolitionists sought to shape American political debate for decades. Early abolitionists encouraged state and federal politicians to adopt a range of antislavery laws. In the revolutionary era, for instance, northern abolitionists pressured political leaders in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island to pass gradual emancipation statutes. Yet the growth of slavery during the 19th century convinced some abolitionists to form their own political party. This very idea divided the antislavery movement. Led by William Lloyd Garrison, militant abolitionists (largely concentrated in the northeast) argued that the American political system was corrupt and that any abolitionist political party would lose its moral bearings by competing for votes in state and federal elections. A sizable contingent of abolitionists — located largely in New York, Ohio, and the expanding Midwest — disagreed with Garrison. In 1840, they formed the Liberty Party, the nation’s first official antislavery party. Over the next decade, it ran antislavery candidates for state gubernatorial offices, the federal Congress, and the presidency. Capturing a small percentage of voters in various elections during the 1840s and 1850s, the Liberty Party nevertheless had particular strengths in New York and Ohio. In the election of 1844, for example, New Yorkers cast enough ballots for the Liberty Party presidential candidate James Birney that the Empire State’s electoral college votes went to (slaveholding) Democrat James K .Polk instead of the even more reviled slaveholding Congressman Henry Clay. While they were unsuccessful in many elections, Liberty Party candidates made antislavery politics — as opposed to moral protest — a visible part of American life. Indeed, the Liberty Party paved the way for subsequent antislavery political parties, even if these parties were not strictly abolitionist. Read the political platform for the Liberty Party here. The Free Soil Party, formed in 1848, garnered many more voters than the Liberty Party by emphasizing opposition to slavery’s territorial expansion rather than abolition in the South. Similarly, the Republican Party, formed in the mid-1850s, largely sought to halt slavery in the West. Still, the Free Soil and Republican parties grafted antislavery ideas onto the American political system. By the Civil War era, even the most hardened abolitionist — such as William Lloyd Garrison — came to support the Republican Party as a bastion of antislavery action.

Lesson Plans

Protesting the Fugitive Slave Act: Fighting Back for Freedom – Abolitionists in southeastern Wisconsin battled against the Fugitive Slave Act by employing print culture. Students will read through an abolitionist broadside and evaluate the ways that abolitionists attempted to influence public opinion.